Người dân Mỹ biết taị sao họ tham chiến ở Pearl Harbor năm 1941, ở Triều

Tiên năm 1950. Nhưng hình như họ không hiểu tại sao xứ họ lún vào “vũng

lầy” chiến tranh Việt Nam từ 1954 đến 1975. Từ chiến trưòng Việt Nam xa

xôi, quan tài liên tiếp trở về. Khi nốt nhạc chiêu hồn còn đang lơ lửng,

bên nấm mồ phủ hoa và lá cờ đầy kịch tính, gia đình tử sĩ giật mình “Sự

thật ở đâu? Ngưòi anh hùng không toàn thây kia nằm xuống cho ai?” Tướng

McArthur nói “Old soldiers never die; they just fade away/Ngưòi lính già

không chết; họ chỉ nhạt dần đi”. Có lẽ phải thêm “Soldiers never lose,

but are betrayed/ Người lính không bao giờ thua trận/họ chỉ bị phản

bội”.

Cựu quân nhân Việt Mỹ giống nhau một điểm: ồn ào nhận thua trận mà quên

rằng:

Chỉ cấp lãnh đạo mới thua trận!

Chỉ cấp lãnh đạo mới phản bội!

Nhưng cấp lãnh đạo chiến tranh Việt Nam là ai?

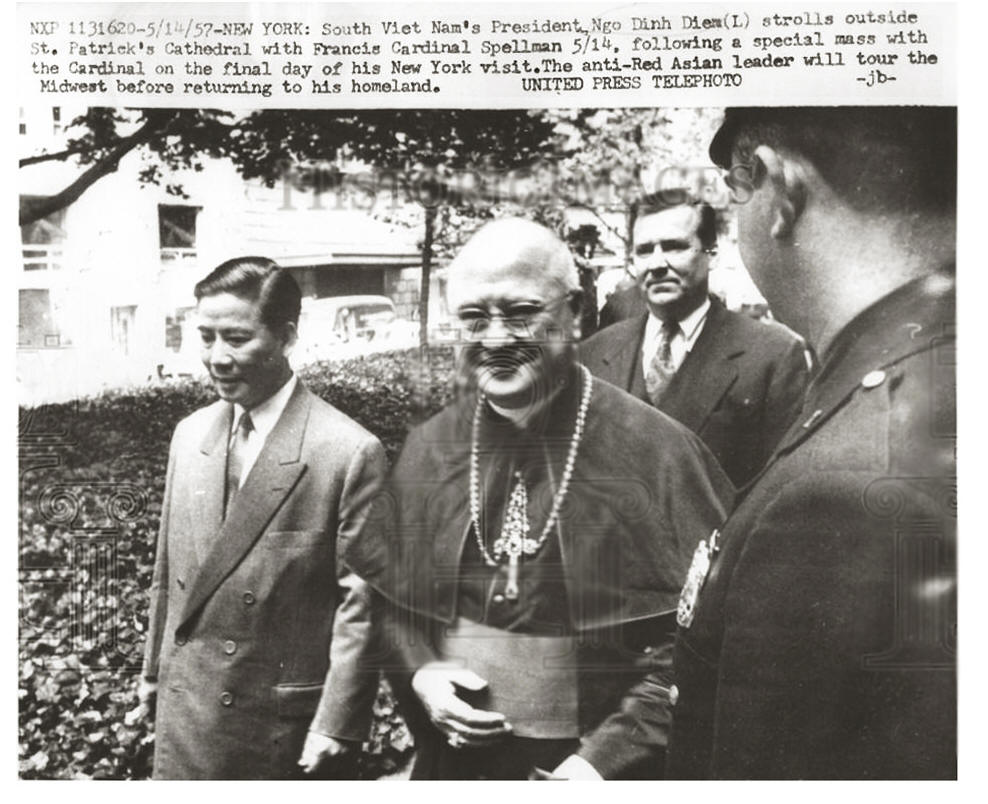

Lúc người dân Mỹ khám phá ra rằng khi chấp nhận chiến tranh thì phải

chấp nhận hy sinh nhưng Hồng Y Spellman chỉ muốn ngườì “hy sinh’ cho

ngài, họ bắt đầu biểu tình trưóc nhà thờ St. Patrick và tư dinh của ngài

ở New York. Lần đầu tiên tên một hồng y được đặt tên cho cuộc chiến,

“Spellman’s War.” Những bài viết cay đắng về ngài khá nhiều. Có một điều

người dân Mỹ “cay đắng” về cuộc chiến Việt Nam: đang từ một dân tộc anh

hùng kiểu “vì dân diệt bạo”, họ trỏ thành hiếu chiến hiếu sát, trong khi

đó, Vatican được tiếng là rao giảng hoà bình. Ý kiến của một cựu chiến

binh “Hơn 58,000 lính Mỹ không biết rằng họ chết ở Việt Nam cho Giáo Hội

Ki-tô. Không đi lính, thì đi tù 5 năm. Biết vậy, tôi không đăng lính năm

1968. Tôi sẽ đi biểu tình chống chiến tranh và ngồi tù trong danh dự để

thách đố nhũng láo khoét của chính phủ về tình hình VN.”

Điều đau của quân nhân Mỹ-Việt, từ tướng cho đến quân trong cuộc chiến

ViệtNam: đào ngũ thì bị tù, muốn đánh cũng không đuợc, muốn thua cũng

không xong, muốn thắng lại càng khó! Chết uổng đời, sống bị phỉ nhổ! Khi

siêu quyền lực muốn kéo dài chiến tranh để tiêu thụ võ khí, thì xác

người chỉ là con số, Việt Nam là nấm mồ, chôn ai không cần biết.

Trong 28 năm làm hồng y, hồng y Spellman trực tiếp can dự vào cuộc chiến

Việt Nam suốt 13 năm – từ 1954 đến 1967. Tuy có tới hơn ba triệu Người

Việt-Mỹ chết “Cho Ngài, Do Ngài và Vì Ngài”, mặc dù tên tuổi của ngài

hình như còn rất xa lạ với người mình, ngoại trừ một số du học sinh ở

Úc, Mỹ… những năm 1960, bật TV lên là thấy ngài.

Nhưng hồng y Spellman là ai?

Francis Spellman

Truyền thông Hoa Kỳ ghi chép đầy đủ cuộc đời và sự nghiệp hồng y

Spellman (1989-1967). Quan điểm của những tác giả độc lập này khá khách

quan, khi chỉ muốn tìm ra “sự thật”, tìm ra “mục tiêu tối thưọng” cuả sự

việc. Họ không tìm cách bào chữa/tâng bốc/đạp đổ nhân vật, mà chỉ phân

tích mục tiêu cho cho ra lẽ. Tác giả Avro Manhatttan còn cẩn thận viết

“Đề cập đến “giáo hội Ki-Tô” cuốn sách của tôi không nhắm đến những tín

đồ thuần thành, không biết chút xíu gì về những âm mưu toan tính nói

trên, chỉ nói đến giới lãnh đạo cao cấp ở Vatican và những tu sĩ Dòng

Tên”.

Bài viết này chỉ nhặt những chi tiết có liên quan xa gần tới chiến tranh

Việt Nam, còn những sự việc khác như ngài là người đồng tính

(homosexual), chiếm giải quán quân trong việc phát triển giáo hội qua

việc xây dựng trường học Công giáo trên toàn thế giới, thành công vượt

bực trong kinh doanh “Knights of Malta”, thiết lập Ratlines giúp đám

Nazis Đức Quốc Xã chạy trốn, thành tích quậy phá các xứ Trung Mỹ…không

liên quan gì đến vận mệnh ngườì Việt cả.

Có thể nói đường hoạn lộ cuả ngài thẳng băng như một cây thước kẻ.

1. Về tôn giáo:

Năm 1911, chủng sinh Spellman/dòng Jesuits (tức dòng Tên), 22 tưổi tu

học ởRome được hân hạnh kết bạn rất thân với Hồng Y Eugenio Pacelli.

Hồng y gọi yêu cậu là “Frank hay Franny”. Trong 7 năm, hồng y Pacelli đi

khắp thế giới đều mang Frank theo, từ leo núi Alps đến bãi biển Hy Lạp.

Tháng 7-1932, Frank đưọc phong làm giám mục giáo phận Boston, thủ đô

tiểu bang Massachssetts.Chính hồng

y Pacelli, lúc đó là bộ trưởng ngoại giao, tấn phong cho Frank trong một

buổi lễ trọng thể cử hành ở đền thờ Thánh Phêrô/St. Peter’s Basilica ở

Vatican, Frank mặc aó lễ màu vàng chói mà hồng y Pacelli mặc năm xưa.

Lần đầu tiên một giám mục Hoa Kỳ được hân hạnh này, giáo dân Boston nở

nang mặt mũi.

Tháng 3-1939, hồng y Pacelli được bầu làm gíao hòang Pius XII. Đúng tám

tuần lễ sau, giáo hoàng Pius XII phong cho Spellman làm tổng giám mục

New York, giáo phận giầu có nhất Hoa Kỳ. 20 năm sau, hồng y Spellman

biến New York thành giáo phận giầu nhất thế gìới. Cùng năm 1939,

Spellman đuợc phong chứctổng tuyên úy quân đội: cái vé tối danh dự đặt

giám mục Spellman trên đỉnhmạng lưói siêu quyền lực gồm siêu quí tộc/tài

phiệt/chính trị/tình báo/quân sựliên quốc gia có tên Sovereign Military

Order of Malta, viết tắt SMOM, hội viên phải được giáo hoàng sắc phong.

Nội cái tên không thôi đã nói lên mục đích của SMOM.

Năm 1946, giáo hoàng Pius XII phong Spellman chức hồng y. Không cần mọc

cánh, ngài trở thành “thiên thần” giữa Vatican và bộ ngọai giao Mỹ. Ở

Mỹ, người ta linh đình chúc tụng ngài là American Pope/Giáo Hoàng Hoa

Kỳ. Ở Vatican, Người ta gọi ngài là Cardinal Moneybags/Hồng Y Túi Tiền.

Ngôi thánh đường Patrick ngài ngự đuợc gọị chệch đi là

“Come-on-wealthCommonwealth”), trở thành thời thượng. Ngài làm lễ cưới

cho Edward Kennedy ở đó. Avenue/Đaị lộ Của Cải Nhào Vô” (thay vì “

2. Quyền lực:

Đóng góp tài chánh của hồng y Spellman cho Vatican, tình bạn với Giáo

hoàng Pius XII, vị trí chót vót trên đỉnh SMOM, quyền lực Spellman hầu

như vô tận không ai dám đụng. Bạn của ngài nằm trong danh sách 100 người

quan trọng nhất thế kỷ 20. Ngài giới thiệu với giáo hoàng Pius XII hàng

loạt các nhà cự phú, biến họ thành quí tộc Hiệp sĩ Malta, không ai dám

đụng tới. Hốt tiền chỗ này bỏ chỗ kia khéo léo như một bà chủ hụi, dưới

bàn tay Spellman mọi việc trôi êm. Thay vì nộp tiền niên liễm cuả

Knights of Malta- Hiệp sĩ Malta vào tổng hành dinh SMOM ở Rome, Spellman

chuyển tiền đó vào tài khoản riêng cuả hồng y Nicola Canali (1939-1961)

bộ trưỏng bộ ngoại giao Vatican. Vài câu hỏi yếu ớt vang lên, ngài không

bận tâm trả lời. Báo nào xa gần hơi “tiêu cực” về ngài, ngài cho lệnh

các cửa hàng sang trọng khu Sak Fifth Avenue rút hết quảng cáo liền một

khi. Thương xá Sak Fifth/New York chỉ là một tài sản khiêm nhường của

ngài, cũng như tổng giám mục Ngô Đình Thục là chủ thương xá Tax/Saigon.

Hồng y Spellman giúp Vatican 1 triệu đô la tài trợ Công đồng Vatican II

nhưng ngài không hơi sức nào bầu bạn với nhũng kẻ nghèo khó. Tháng

3/1949, hai trăm phu đào huyệt nghĩa trang Calgary – rộng 500 mẫu mà

ngài là chủ nhân – đòi tăng lương 20% từ 59.40 lên 71.40 $USD (một

tuần). Ngài không chấp nhận, ngày mím môi bắt các chủng sinh nhà thờ St.

Patrick thay thế, đào huyệt chôn 1020 quan tài xếp lớp. Ngài đổ cho cái

đám cùng khổ ấy là bọn… cộng sản. Mấy Người vợ nghèo khổ của đám phu đào

huyệt mếu máo phân trần “Chồng tôi chỉ muốn tăng lương, không biết cộng

sản là gì”.

3. Về chính trị:

Hồng y Spellman đìều khiển thế giớí bằng điện thoại. Ngài cho hay trước

sẽ không ai viết được tiểu sử ngài, vì sẽ không bao giờ có dấu vết chứng

từ. Ngài là cố vấn của năm đời tổng thống Mỹ từ 1933 đến 1967, từ

Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy đến Johnson. Ngài là bạn thân với

tưóng William Donovan – xếp sòng OSS, tiền thân CIA. Donovan chỉ định

Allen Dulles nối ngôi CIA, nên hai anh em nhà Dulles, bộ trưởng ngoại

giao và giám đốc CIA, cũng dưới tay ngài.

Một trong những ngưòi bạn danh giá là đại gia Joseph Kennedy, thân phụ

của thượng nghị sĩ trẻ tuổi John Kennedy/tiểu bang nhà, Mass. Năm 1935,

taì sản ông Kennedy đã lên tới $180 triệu đô la, khoảng 3 tỷ bây giờ.

Sau thế chiến II, một trong những chiến lược của Vatican trong việc ngăn

chặn cộng sản bằng cách ủng hộ các ứng viên phe Dân Chủ Ki-Tô giáo. Đang

khi Vatican muốn có một tổng thống Ki-tô ở tòa Bạch Ốc, đúng lúc Joseph

Kennedy muốn John Kennedy làm tổng thống. Giáo hoàng Pius XII gưỉ bác sĩ

riêng Riccardo Galeazzi đến gặp Spellman và Joseph Kennedy để thương

lượng. Có tiền mua chức tổng thống dễ như mua bắp rang.

Những yếu tố trên chín mùi cùng lúc, Spellman dựa vào Vatican dựng lên

hai tổng thống Ki-tô dân chủ đầu tiên: John F. Kennedy ở Washington D.C

cũng như Ngô Đình Diệm trước đó ở Saigon.

Tài liệu ngoại quốc không có những chi tiết như trong bài viết “Có phải

Hoa Thịnh Đốn Đã Đưa Ông Diệm Về Làm Tổng Thống Đệ Nhất Cộng Hoà VN”cuả

Linh mục An-Tôn Trần Văn Kiệm. LM là người duy nhất ở gần ông Ngô Đình

Diệm trong hơn hai năm ông Diệm ở Mỹ, Theo Linh mục, có ba người đưọc

hồng y Spellman bảo trợ, nhận làm con nuôi: hai linh mục Trần Văn

Kiệm-Nguyễn Đức Quý và ông Ngô Đình Diệm.

(Ghi chú: ông Ngô Đình Diệm có tói ba vị “cha nuôi” oai quyền một

cõi: thượng thư Nguyễn Hữu Bài, Hồng y Spellman và trùm CIA Allen

Dulles)

Năm 1951, đang ở New York, Linh mục Trần Văn Kiệm, được điện tín từ Âu

châu ra đón tổng giám mục Ngô Đình Thục và em là Ngô Đình Diệm taị phi

trường Idlewild (phi trường Kennedy bây giờ). Sau đó Hồng y Spellman gửi

ông Diệm trú taị nhà dòng các linh mục Maryknoll, New Jersey. Tuy đuợc

Hồng y Spellman giầu có bảo trợ, ông Diệm không đưọc Hồng y cho đồng xu

nào. Suốt hai năm, chỉ một mình Linh mục Kiệm thăm viếng, bao biện việc

di chuyển, kể cả thuê khách sạn cho ông tiếp khách vì biết ông rất thanh

bạch. Cho đến tháng 6/1953, ngày ông từ giã Hoa Kỳ qua Pháp gặp hoàng đế

Bảo Đại trước khi về VN nhận chức thủ tướng, Linh mục M Trần Văn Kiệm và

năm Người bạn còn chạy mua vội cho ông chiếc cà vạt màu xanh.

Tuy vậy, theo linh mục Trần Văn Kiệm, mãi đến giữa năm 1953, chính giới

Mỹ chẳng biết gì về ông Ngô. LM TVKiệm viết:

-”Có lần chính khách Mỹ phàn nàn với tôi: linh mục đề cao tư cách lãnh

đạo của ông Ngô Đình Diệm, và cả Đức Cha Ngô Đình Thục cũng làm như thế,

nhưng chúng tôi cần thêm chứng nhân, vì Đức Cha Thục là anh đề cao em

thì có chi là lạ”.

-”Mãi tới gần một tháng sau khi trận Điện Biên phủ nổ lớn ngày 13 tháng

3 năm 1954 (thất thủ ngày 26 tháng 6) và có lẽ cũng vì nghe lời Đức Hồng

y Francis Spellman kêu gọi, ngày mùng 7 tháng tư năm 1954 tổng thống

Eisenhower mới lên tiếng cảnh giác, khi ông xướng lên chủ thuyết Domino:

“Nếu Việt Nam sụp đổ trước sức tấn công Cộng sản quốc tế với Liên Xô và

Trung hoa yểm trợ Hà nội, thì mấy nước ở Đông Nam Á sẽ khó mà đứng vững

được”.

Hồng Y Spellman Dựng nên Đệ Nhất Cộng Hòa VN

Một chân ở điện Capitol, một chân ở Vatican, hồng y Spellman ảnh hưởng

cả tổng thống Mỹ, sai khiến được trùm CIA, hoạch định chính sách cho bộ

ngoại giao, nên ngài yên chí sẽ được bầu làm giáo hoàng ở Vatican khi

bạn thân ngài là giáo hoàng Pius XII qua đời. Không ngờ, ngày

28-10-1958, người đựợc bầu là Hồng Y Angelo Roncalli, tức Giáo hoàng

John XXIII. Hồng y Spellman giận lắm, nhiếc sau lưng ông: “Ông ta đâu

xứng làm Giáo Hòang, Ổng đáng đi bán chuối/He’s no Pope. He should be

selling bananas”.

Hồng y Spellman có vẻ như lập laị câu nói cuả Cesar “Veni, Vidi, Vici”.

Những năm 1950, chính khách Mỹ nói về châu Á còn lọng cọng dở bản đồ,

Spellman đã đi qua cả rồi. Năm 1948, ngài đỡ đầu cho linh mục Fulton

Green quaAustralia đọc diễn văn tại nhà thờ St. Mary’s ở Sydney.

Spellman ghé Singaporevà Bangkok, bay ngang Angkor Wat. Trên đưòng trở

về Mỹ, trứơc khi bay quaCanton và Hongkong, ngài tiện chân ghé Saigon.

Tổng giám mục Saigon người Pháp Jean Cassaigne có mời tổng giám mục

Vĩnh-Long Ngô Đình Thục trong buổi tiếp đón ngày 25-5-1948: từ buổi

“tiện chân”định mệnh này, số phận cuả dòng họ Ngô-Đình đã an bài.

Giới học thuật Mỹ – tôn giáo, chính trị, truyền thông, giáo dục – đồng ý

dứt khóat 100% về vai trò của Hồng Y Spellman trong việc dựng lên tổng

thống Ngô Đình Diệm. Xin chỉ giới hạn vào bốn tác giả mà sách của họ đã

được thử thách với thờì gian. Trong số bốn Người này, hai là linh mục

Ki-tô giáo:

– Theo Wilson D Miscamlble, giáo sư môn sử/đaị học Notre Dame/Indiana,

trong bài viết “Francis Cardinal Spellman and Spellman’s War”, lý do

người Mỹ nhúng tay vào chiến tranh VN bắt nguồn từ ChiếnTranh Lạnh kéo

dài từ châu Âu. Dưới ảnh hưởng vô cùng to lớn của Spellman, chính giới

Mỹ đều tin tưởng rằng sự bành trướng của khối Cộng Sản Liên Sô và đồng

minh của họ, Bắc VN, là mối đe dọa trực tiếp nước Mỹ.

– “The American Pope: The Life and Times of Francis Cardinal Spellman”,

tác giả John Cooney (cây bút cuả Wall Street Journal) viết: “Nếu không

có Spellman ủng hộ Ngô ĐìnhDiệm hồi 1950, chắc chắn không có chính phủ

miền Nam Việt Nam.” Cooney dành 18 trang riêng về Spellman và Việt Nam.

Tờ Church & State phê bình “dẫn chứng kỹ càng, tất cả người Mỹ nên đọc

và học hỏi”

– “An American Requiem/Kinh Cầu Hồn Nước Mỹ”, tự truyện, tác giả James

Carroll có bố là trung tá tình báo Pentagon: chuyên viên tìm toạ độ để

ném bom ở Việt Nam, mẹ lại là bạn thân cuả hồng y Spellman. Ông viết

“Chiến tranh VN bắt đầu từ Spellman”, sách-bán-chạy nhất 1960-70, đoạt

National Book Award for Non-Fiction (1996), giải thưởng cao quí nhất cuả

văn học Mỹ. Carroll dành nguyên chương 8, “Holy War/Cuộc Chiến Thần

Thánh” cho chiến tranh Việt Nam.

– Theo linh mục Martin Malachi: Spellman dấn thân vào Việt Nam là theo ý

muốn của Giáo Hoàng Pius XII: muốn ngưòi Mỹ đưa ông Ngô Đình Diệm lên vì

ảnh hưởng của tổng giám mục Ngô Đình Thục.

(Ghi chú: Linh mục Malachi, giáo sư Giáo hoàng Học Viện Vatican

(Pontifical Biblical Institute) từ 1958 đến 1964, cùng thờì điểm chìến

tranh Việt Nam. Ông là phụ tá, thư ký riêng, thông dịch viên cho hồng y

Augustin Bea/dòng Jesuit và cho Giáo hoàng John XXIII. Ông ở cùng dinh

vơí giáo hoàng John XXIII, được giao phó nhiều việc “nhậy cảm. Là linh

mục dòng Jesuits/dòng Tên trong 25 năm, năm 1965 ông xin chấm dứt ơn kêu

goị, nghiã là ra khỏi dòng Jesuits. Ông qua New York, sống lang thang

làm bồi bàn, tài xế taxi, rửa chén. Hai năm sau ông bắt đầu kiếm ăn bằng

viết sách. Cuốn nổi tiếng nhất: “The Jesuits: The Society of Jesus and

the Betrayal of the Roman Catholic Church/ Dòng Jesuit và Sự Phản Bội

Của Giáo Hội La Mã”).

(Cả ba cuốn The American Pope, An American Requiem, The Jesuits đều có

trên amazon.com.)

Có thể tóm tắt: đưọc các nhân vật tối cao cuả lập pháp, tư pháp, tình

báo, taì phiệt và tôn giáo Hoa Kỳ đã nâng đỡ con đường hoạn lộ cuả ông

quan Á Châu Ngô Đình Diệm giống như truyện cổ tích Cô Bé Lọ Lem, ngọai

trừ đoạn cuối.

1. 1951: taị New York, Hồng

Y Spellman giới thiệu ông quan-tự lưu vong-Ngô Đình Diệm với chính giới

Mỹ, gồm thượng nghị sĩ Michael Mansfield, thẩm phán tối cao pháp viện

William O. Douglas, trùm CIA Allen Dulles, cha con Joseph Kennedy, tất

cả là tín đồ công giáo.

2. 1954: CIA gửi Edward

Landsdale qua Saigon hóa phép “trưng cầu dân ý” truất phế Baỏ Đaị-ủng hộ

thủ tứơng NĐDiệm. Landsdale đề nghị tỷ lệ đắc cử là 70%, ông Diệm không

đồng ý, đòi phải đạt được 98.2%, con số cao hơn cả số cử tri ghi danh.

3. 1955: Bộ Ngoaị Giao gửi

đoàn cố vấn dân sự qua Saigon (giáo sư Wesley Fishel/đại học Michigan

cầm đầu) soạn cấu trúc cho an ninh, kinh tế, giáo dục, hành chánh, soạn

cả hiến pháp cho Việt Nam Cộng Hòa. Cơ quan USAID/Sở Thông tin Hoa Kỳ

phát không tờ Thế Giới Tự Do, lò sản xuất những khẩu hiệu như “tiền đồn

chống cộng, lý tưởng tự do, Người quốc gia…”. USAID cũng bao dàn trọn

gói luôn tờ The Times bằng tiếng Anh của ông Ngô Đình Nhu.

4. 1955: chính phủ

Eisenhower tài trợ 20 triệu đô la cho quĩ [Roman] Catholic Relief

Services , “Cơ Quan Viện Trợ Công Giáo”. Hồng y Spellman cũng đích thân

viếng Saigon và tặng $100,000 cho quỹ này, giúp tái định cư ngưòi di cư

(có tài liệu ghi $10,000). Từ đó mỗi năm, Hoa Kỳ viện trợ khoảng 500

triệu đô la một năm cho Việt Nam Cọng Hòa.

5. Ngoài cố vấn Mỹ

chính thức tạị dinh Độc Lập, Spellman còn gàì điệp viên kiểm soát hai

anh em ông Diệm-Nhu.

6. Từ đầu năm 1963, Spellman bắt đầu tách rời khỏi Ngô Đình Diệm

khi chính phủ Diệm từ chối không cho thêm quân nhân Hoa Kỳ vào Việt Nam.

7. Ngày 7-9-1963 tổng giám mục Ngô Đình Thục rời Việt Nam qua Roma,

bước lưu vong đầu tiên, không được giáo hoàng Paul VI tiếp. Ngày

11-9-1963 Ngô Đình Thục bay qua New York cầu cứu, hồng y Spellman lánh

mặt đi Miami Beach/Florida dự lễ gắn huy chưong.

8. Ngày 1-11-1963: Spellman bật đèn xanh cho âm mưu dứt điểm con

nuôi Ngô Đình Diệm. Từ đó, Spellman không hề nhắc đến tên Thục-Diệm thêm

một lần nào nữa.

9. Spellman tiếp tục đìều khiển guồng máy chiến tranh Việt Nam

không-Diệm cho đến khi về hưởng nhan thánh Chuá năm 1967.

Hồng Y hay đaị tướng?

Đáng lẽ Hồng y Spellman phải theo nghiệp binh đao. Năm 1943, chỉ trong

bốn tháng, ngài vượt 15,000 miles, đến 16 quốc gia vừa là đại diện của

Vatican, vừa là tổng tuyên uý quân đội, vừa là đặc sứ cuả tổng thống

Roosevelt. Ngài khéo léo luôn để Vatican đứng ngoài, và đứng trên chìến

tranh. Ngài đuợc West Pointtrao tặng huy chương. Ngàì có bằng lái máy

bay cả ở Italy lẫn Massachussets.

Fidel Castro mô tả hồng y Spellman là “Giám mục của Ngũ Giác Đài, của

CIA và FBI”. Tổng thống Mỹ còn sợ bị ám sát, Spellman thì không. Trong

cuốn “Vietnam… Why Did We Go? “Vì Sao Chúng Ta Đã Đi Việt Nam” tác giả

Avro Manhattan chứng minh “siêu quyền lực” giết tổng thống John Kennedy

chính là Hồng y Spellman. Bản dịch tiếng Việt, có trên internet, dịch

giả Trần Thanh Lưu.

Hậu thuẫn lớn của hồng y Spellman cho chính quyền Lyndon Johnson không

phải ở châu Mỹ La Tinh, mà ở Việt Nam. Dù ở tuổi nào ngài cũng thich làm

“anh là lính đa tình”. Ngaì thường xuyên gặp gỡ các ông tướng ở tòa Bạch

Ốc, có mặt tại những phiên họp mật của tình báo. Ngài họp với Ngũ Giác

Đài, bàn cãi chiến thuật/chiến lược với hàng tướng lãnh. Phiên họp cuối

ngài tham dự, tháng 3/1965, tại Carlisle một trưòng huấn luyện quân sự ở

Pensylvania. Ngài cho tiền các giáo hội địa phương, nguồn cung cấp tin

tức vô tận. Khi cần ngài hỗ trợ cho CIA và FBI khiến hai cơ quan này

khép nép dưới chân ngài. Họ không sao có được mạng lướí rộng lớn, miễn

phí và trung thành như giáo dân. Trong khi hồng y Spellman chỉ phán một

câu, các giáo hội địa phương xa xôi nghèo nàn mừng mừng tủi tủi, vứt cả

tổ tiên ứng hầu thánh ý.

Linh mục William F. Powers viết “Hình như Hồng Y Spellman đến Việt Nam

để ban phép lành cho những khẩu đại bác, trong khi giáo hoàng John 23

đang năn nỉ phải cất chúng đi. Ngài sang thăm lính Mỹ ở Việt Nam trong

binh phục kaki vàng. Có lần, vừa trở về từ mặt trận VN, “áo anh mùi

thuốc súng” ngài lập tức bay đến Washington dùng cơm trưa với tổng thống

Johnson, có cả mục sư Billy Graham (đuợc coi như Giáo hoàng Tin Lành ở

Mỹ). Tổng thống hỏi ý cả hai ngài bước kế tiếp phải làm gì. Trong khi

mục sư Graham còn đang lúng túng giữ yên lặng, HY Spellman không ngần

ngaị, nói liền một câu lạnh cẳng “Thả bom chúng! Chỉ việc thả bom

chúng!” Và Johnson đã làm theo lời cố vấn cuả ngài. [Thus, when Johnson

asked both Spellman and Billy Graham at a luncheon what he should do

next in Vietnam, Graham was uncomfortably silent. “Bomb them!” Spellman

unhesitatingly ordered. “Just bomb them!”’ And Johnson did]. Chúng là

ai? Là người Việt. Chưa được đọc bài nào của tác giả Việt về câu nói

kinh hãi này. Chỉ mới thấy tác giả Nguyễn Tiến Hưng giận dữ về câu “Sao

chúng nó không chết phứt đi cho rồi” cuả ông Henry Kissinger.

Billy Graham (1918-) đâu phải tay mơ. Ông được coi như “giáo hoàng Tin

Lành,” cố vấn các tổng thống Mỹ từ đời Eisenhower đến G. Bush. Ông rất

oai, quở trách tổng thống Richard Nixon như con cái trong nhà. Có lẽ

thấy Spellman ngon lành quá, Graham bắt chưóc y chang khiến ông cũng rất

nổi tiếng trong quân sử Hoa kỳ với lá thơ 13 trang: Năm 1969 Graham đến

Bangkok gặp gỡ vài “nhà truyền giáo” từ VN qua. Các đaị diện Chúa sau

khi làm dấu thánh giá, đề nghị nếu hội nghị hoà bình Paris thất bại,

Nixon nên dội bom các đê điều ở Bắc Việt. Không rõ các nhà truyền giáo

này kiêm điệp viên hay điệp viên kiêm nhà truyền giáo, họ là người Việt

hay ngưòi ngoaị quốc, thuộc dòng nào, từ đâu qua Bangkok gặp Graham… rất

tiếc bản tin không nói rõ. Trở về Mỹ, Billy hăng hái gửi 13 trang viết

tay đề ngày 15-4-1969 cho tổng thống Nixon “dội bom các đê Bắc Việt Nam,

chỉ trong một đêm thì kinh tế ở đó tiêu đìều liền hà”. Bức thư này đuơc

bạch hóa tháng 4/1989.

Tạ ơn Chúa, Alleluia!! “Dội bom đê điều” giết cả triệu dân là tội ác

chiến tranh! Người Mỹ phải hành quân đáng mặt nưóc lớn. Họ không quên án

lệ Arthur Seyss-Inquart, luật sư ngườì Đức, sĩ quan Phát xít cuả Hitler.

Ngày 16-10-1946, toà án quốc tế xử treo cổ ông này và 10 người khác vì

phá hủy đê ở Hoà Lan trong thế chiến II. Trưóc khi chết, Seyss-Inquart

còn nói kiểu sân khấu: “Hy vọng cuộc hành hình này là thảm kịch cuối

cùng cuả thế chiến II mà bài học sẽ là hoà bình và hiểu biết giữa con

người.” Tử tội xin “trở laị đạo”, đuợc xưng tội và chiụ đủ các phép bí

tích. Kể cũng hay, giết ngưòi xong xưng tội là linh mục tha tội ngay,

Chúa có tha không tính sau. Có hơi thắc mắc không biết ông có tái sinh

làm Ki-tô hữu chưa.

Wilson D. Miscamble kết luận về “sự nghiệp” cuả hồng y Spellman như sau:

Lòng ái quốc mù quáng đã ngăn cản ông tự hỏi một điều rất quan trọng

“mục đích của chiến tranh là gì?”Ông cũng không thèm biết đến “phương

tiện và hậu quả”.

Ông không hề biết rằng những báo cáo của chính phủ về Việt Nam là lừa

gạt.

Ông không bao giờ biết đến nhân mạng và tiền bạc trả cho cuộc chiến tính

đến 1967.

Ông cũng không bao giờ phản đối cách nước Mỹ tiến hành cuộc chiến. Ngược

lại ông là người cổ võ việc ném bom Bắc Việt Nam.

Cuối cùng, ông không bao giờ tỏ ý hối tiếc về vai trò cuả ông. Sự thiệt

hại nhân mạng do việc dội bom cũng không hề dấy lên trong ông bất cứ một

tình cảm nào. Đó là điều đáng trách nhất, vì ông là một đấng chủ chăn.

Theo nhà tranh đấu Lê Thị Công Nhân:

“Sự kiện 30-4-75 thì tôi không phải là chứng nhân của sự kiện đó vì tôi

sinh ra vào năm 1979 nhưng với những gì mà tôi trực tiếp trải qua, và

tôi chịu đựng trên đất nước Việt Nam, tôi thấy đây là 1 sự kiện hết sức

đặc biệt và cá nhân tôi nghĩ rằng đây là

sự an bài nghiệt ngã của Đức Chúa Trời dành cho dân tộc Việt Nam”.

Cứ dâng vạn nỗi đau thương lên cho Chúa, người cũng sẽ im lặng như ngàn

năm nay, như khi dân Do Thái cuả Chúa bị tận diệt. Đổ cho Chúa, Việt

Cộng mừng vì “Chúa an bài như thế, khỏi tranh đấu nữa”. Hồng y Spellman

mừng, Cộng sản quốc tế mừng, tư bản mừng! Cứ làm đi rồi đổ hô cho Chúa.

Nhưng một khi bom đạn và tổn thất sinh mạng cân đong đo đếm được thì

nguyên nhân/thủ phạm cần phải được xem xét kỹ lưỡng. Dù không làm kẻ

chết sống lại, người mù sáng mắt, nhưng ít ra học được vô số bài học.

Nếu không, chắc chắn quá khứ sẽ lập lại thêm lần nữa.

Có khi đang lặng lẽ xảy ra cũng nên!

Trần Thị Vỉnh Tường

[Nguồn: tạp chí SàiGòn Nhỏ, số 1265, ngày 22 tháng 10 năm 2010, Ấn bản

Orange County, trang A1]

DREW PEARSON

Cardinal Spellman And The Viet War

WASHINGTON There was much more than meets

the eye behind the flareup between Francis Cardinal Spellman, the

persuasive, powerful Catholic cleric of New York, and Pope Paul IV,

whose pacific philosophy is supposed to guide the Catholic church. There

have been differences between Spellman and the Vatican before, dating

back to Pope John, also differences between Spellman and the hierarchy

in the United States. In November the Conference of Catholic Bishops

refused to take Spellman’s all-out war stand, and only last week Richard

Cardinal Cushing in Boston made it clear that he stood firmly with the

Pope in his efforts for peace, not with Cardinal Spellman who called for

"total victory,” in a war in which he said American troops arc fighting

as “soldiers of Christ.” The oasic difference between the Pope and

Spellman gets down to the reasons why in some diplomatic circles, the

war in Vietnam is called "Spellman's war”, not "Christ’s war.” "It will

come as a surprise to the American people that our soldiers have

enlisted in the war as soldiers of Christ, said Sen. Wayne Morse, DOre.

They have doubtless forgotten that it was Cardinal Spellman who arranged

for a public relations firm to build up President Diem as the Catholic

puppet of South Vietnam. and that Diem’s brother, the Catholic bishop of

Saigon, beat a well-worn path to Spellman’s door to "promote the war.”

With more American troops now in Southeast Asia than we had in Korea and

with the Pope in complete disagreement with the cardinal of New York,

it’s important at this time to review the chronological steps by which

we got into the so-called "Spellman war.” Step No. 1 took place in

April. 1954, as the French faced certain defeat. Vice President Nixon at

the April meeting tof the American Society of Newspaper Editors told

them, off the record, that Eisenhower planned to send troops to

Indo-China. A leak caused such critical public reaction that the move

was abandoned. Step No. 2 occurred later that year as the French

prepared to withdraw and the Geneva Conference was called to save

France’s face. Ngo Dlnh Diem, described as a sort of "Catholic

mandarin.” had been at Maryknoll, the Catholic seminary autside New

York, and was sent by Cardinal 'Spellman to see Sen. John F. Kennedy in

Washington. Sen. Kennedy then made a speech warning against a negotiated

peace which Cardinal Spellman issued this Christmas. Step No. 3

—Cardinal Spellman enlisted the support of Joseph P. Kennedy, wealthy

father of the late President and a heavy contributor to Spellman's

charities. The two had worked together in backing the late Sen. Joseph

McCarthy. They arranged for the crack Harold Oram public relations firm,

at a fee of $3,000 « month, to build up Diem as

the man who could save Vietnam. In

cooperation with the Catholic Relief Agency, Spellman helped organize

“The American Friends of Vietnam” to promote Diem and American aid for

Vietnam. Step No. 4 By this time the Geneva Treaty had cut Vietnam into

the North and South, with elections to be held two years later 1956 to

decide whether they should unite. Cardinal Spellman, through his friend

Vice President Nixon, wanted strong U. S. support for the South.

Spellman had given his blessing to the Eisenhower - Nixon ticket against

Adlai Stevenson. Nixon agreed with him regarding Vietnam; but not

Eisenhower, who told me earlier he would never get American troops

bogged down on the mainland of Asia. At Christmas, 1954, Spellman took

his first trip to Saigon, and handed refugees a $lOO,OOO check from the

Catholic Relief Agency. Back in the United States he sold the Elsenhower

administration on contributing several millions in foreign aid. Step No.

5 Cardinal Spellman addressing the American Legion in 1955, said that

the Geneva Treaty ment “taps” for freedom in South-

east Asia. Step No. 6 Eisenhower finally

yielded to Nixon and sent military "advisers” to South Vietnam. A total

of around 1,000 advisers was permitted under the Geneva Treaty. Step No.

7 The astute Harold Oram had built up Diem as a democrat. His speeches

were liberally dosed with democratic cliches. He was regarded as the

"Father of South Vietnam.” When he became president it was; necessary

for the United States to use special secret police to keep him in power.

As a Catholic in a country which is 80 per cen' Buddhist, he was not

popular in the first place, and his high-handed edicts enforced by

graft-ridden subordinates made him less so. Eventually he was dethroned

and assassinated. Step No. 8 President Kennedy in the fall of 196 1

suffered setbacks at the Bay of Pigs and in his confrontation with

Khrushchev at Vienna, which led to the building of the Berlin Wall. His

advisers state that, in need of a foreign affairs victory, he increased

American troons in South Vietnam from 2,000 advisers to 33,000. That was

how the war started. President Johnson has been increasing U. S. troop

strength ever since.

"Spellman and Kennedy also helped form a

pro-Diem lobby in Washington. The rallying cries were anti-Communism and

[Roman] Catholicism. Through their connections, they soon had a

high-powered committee, which was a lumpy blend of intellectuals and

conservatives.

Two men of national prominence, the

former O.S.S. chief "Wild Bill" Donovan and General "Iron Mike"

O'Daniel, were co-chairmen.

The membership included Senators [John

F.] Kennedy and Richard Neuberger; Representatives Emmanuel Celler and

Edna Kelly; and Angier Biddle Duke, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Max Lerner,

socialist leader Norman Thomas, and conservative Utah Governor Bracken"

[ page 242 ]

THE AMERICAN POPE

240

The Cardinal's message was clear. The

fall of Vietnam brought the day closer when Communists would dominate

the United States. "We shall risk bartering our liberties for lunacies,

betraying the sacred trust of our forefathers, becoming serfs and slaves

to the Red ruler's godless goons," he swore.

The other speakers needed no

introduction: Madame Chiang Kaishek and Admiral Arthur W. Radford, the

chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who was a familiar figure at the

Powerhouse. Both speakers were friends of the Cardinal and shared his

conservative views. Madame Chiang lamented that the Soviets had

corrupted the "minds and souls of those who became its puppets--the

Chinese Communists." Radford asserted that the United States should be

ready to police the world. The audience wildly applauded each speaker,

but it was Spellman who brought them to their feet in a thunderous

ovation. At the conclusion of the meeting, the Cardinal asked the

legionnaires to pray for God's intervention. If Eisenhower wouldn't

listen to Spellman, perhaps he would heed the Almighty. "Be with us,

Blessed Lord," the Cardinal intoned, "lest we forget and surrender to

those who have attacked us without cause, those who repaid us with evil

for good and hatred for love."

The day after the convention the impact

of Spellman's address was noted in the press. New York Daily News

columnist John O'Donnell, for example, reported: "From a political

viewpoint-- global, national and New York State--the speech delivered by

Cardinal Spellman was by far the most significant and important heard

here at the convention....''

Spellman's attack on Ho Chi Minh's

revolution was the first sign of his involvement in the politics of

Vietnam. Though few people knew this, the Cardinal played a prominent

role in creating the political career of a former seminary resident in

New York who had just become Premier of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem. In

Diem, Spellman had seen the qualities he desired in any leader: ardent

[Roman] Catholicism and rabid anti-Communism.

Cardinal Spellman had met Diem in New

York in 1950, when the Vietnamese had been at the Maryknoll Seminary in

Ossining, New York. A staunch [Roman] Catholic from a patrician family,

Diem was at the seminary at the intercession of his brother, Ngo Din

Thuc, a Roman Catholic bishop. A lay celibate and deeply religious, Diem

had cut himself off from the world, especially his war-shredded nation,

and had been known only to a small, politically active circle in the

United States. In his homeland his name had hardly evoked enthusiasm. On

an official level in the United States, Diem was an unknown quantity, a

situation Spellman helped rectify. Diem's background meant that he

inevitably came to the attention of Spellman.

The man responsible for bringing them

together was Father Fred McGuire, the anti-McCarthy Vincentian who

worked for the Propagation of the Faith. A former missionary to Asia,

McGuire's intimate knowledge of the Far East was well known at the State

Department. One day the priest was asked by Dean Rusk, then head of the

Asian section, to see that Bishop Thuc, who was coming to the United

States, met with State Department officials, McGuire recalled. Rusk also

expressed an interest in meeting Diem."35

THE RISE OF AMERICANISM

241

McGuire contacted his old friend Bishop

Griffiths, who was still Spellman's foreign affairs expert. He asked

that Thuc be properly received by the Cardinal, which he was. For the

occasion Diem came to the Cardinal's residence from the seminary. The

meeting between Spellman and Diem may well have been a historic one.

Joseph Buttinger, a prominent worker with refugees in Vietnam, believed

the Cardinal was the first American to consider that Diem might go home

as the leader of South Vietnam."

In October 1950 the Vietnamese brothers

met in Washington at the Mayflower Hotel with State Department

officials, including Rusk. Diem and Thuc were accompanied by McGuire as

well as by three political churchmen who were working to stop Communism:

Father Emmanuel Jacque, Bishop Howard Carroll, and Georgetown's Edmund

Walsh. The purpose of the meeting was to ask the brothers about their

country and determine their political beliefs. It soon became clear that

both Diem and Thuc believed that Diem was destined to rule his nation.

The fact that Vietnam's population was only ten percent Catholic

mattered little as far as the brothers were concerned." Such a step

seemed unlikely. Before World War II Diem had been a civil servant

connected loosely with nationalists. Later, he repeatedly refused to

accept government offices under Emperor Bao Dai; the job he wanted was

Prime Minister, but that had been denied him.

As Diem spoke during the dinner, his two

most strongly held positions were readily apparent. He believed in the

power of the [Roman] Catholic Church and he was virulently

anti-Communist. The State Department officials must have been impressed.

Concerned about Vietnam since Truman first made a financial commitment

to helping the French there, they were always on the lookout for strong,

anti-Communist leaders as the French faded.

After Dienbienphu, Eisenhower wanted to

support a broader-based government than that of Emperor Bao Dai, who

enjoyed little popular support and had long been considered a puppet of

the French and the Americans. Thus U.S. officials wanted a nationalist

in high office in South Vietnam to blunt some of Ho Chi Minh's appeal.

The result was that Bao Dai offered Diem the job he had always

wanted-Prime Minister. Diem's self-proclaimed prophecy was coming true.

He returned to Saigon on June 26, 1954, or several weeks after the

arrival of Edward Lansdale, the chief of the C.I.A.'s Saigon Military

Mission, who was in charge of unconventional warfare. U.S. involvement

entered a new stage.

THE AMERICAN POPE

242

Spellman's Vietnam stance was in

accordance with the wishes of the Pope. Malachi Martin, a former Jesuit

who worked at the Vatican during the years of the escalating U.S.

commitment to Vietnam, said the Pope wanted the United States to back

Diem because the Pope had been influenced by Diem's brother, Archbishop

Thuc.

"The Pope was concerned about Communism

making more gains at the expense of the [Roman Catholic] Church," Martin

averred. "He turned to Spellman to encourage American commitment to

Vietnam." 38

Thus Spellman embarked on a carefully

orchestrated campaign to prop up the Diem regime. Through the press and

a Washington lobby, the problems of confronting anti-Communism in

Indochina became widely known in America. One of the men Spellman aided

in promoting the Diem cause was Buttinger, a former Austrian Socialist

who headed the international Rescue Committee, an organization that had

helped refugees flee Communism after World War II and now helped people

fleeing North Vietnam.

The Geneva Accords provided that people

moving between the north and south should have three hundred days in

which to do so. The refugee problems were enormous. When he visited New

York, Buttinger met with Spellman and explained the situation. The

Cardinal placed him in touch with Joe Kennedy, who arranged meetings for

Buttinger with the editorial boards of major publications such as Time

and the Herald Tribune. Editorials sympathetic to the plight of refugees

fleeing Ho Chi Minh's Vietnam began appearing in the American press.

Spellman and Kennedy also helped form a

pro-Diem lobby in Washington. The rallying cries were anti-Communism and

[Roman] Catholicism. Through their connections, they soon had a

high-powered committee, which was a lumpy blend of intellectuals and

conservatives.

Two men of national prominence, the

former O.S.S. chief "Wild Bill" Donovan and General "Iron Mike"

O'Daniel, were co-chairmen.

The membership included Senators [John

F.] Kennedy and Richard Neuberger; Representatives Emmanuel Celler and

Edna Kelly; and Angier Biddle Duke, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Max Lerner,

socialist leader Norman Thomas, and conservative Utah Governor Bracken

Lee.

Spellman's man on the board was Monsignor

Harnett, who headed the Cardinal's Catholic Near East Welfare

Association and now served as the Vietnam lobby's chief link with the

Catholic Relief Services.

To a large extent, many Americans came to

believe that Vietnam was a preponderantly [Roman] Catholic nation. This

misimpression resulted partly from Diem's emergence as ruler. With the

help of C.I.A.- rigged elections in 1955, Diem abolished the monarchy

and Bao Dai was forced to live in exile. The heavily [Roman] Catholic

hue to the Vietnam lobby also accounted for much of the widespread

belief. Still another factor was [Cardinal] Spellman's identification

with the cause.

THE RISE OF AMERICANISM

243

Then there was the role of a winsome

young [Roman] Catholic doctor working in Vietnam named Tom Dooley. A

navy lieutenant who operated out of Haiphong, Dooley worked with

refugees. At one point Dooley, a favorite of Spellman, even organized

thirty-five thousand Vietnamese Catholics to demand evacuation from the

north. Dooley's efforts were perhaps even more successful in the United

States than in Vietnam. He churned out newspaper and magazine articles

as well as three bestselling books that propagandized both the [Roman]

Catholic and anti-Communist nature of his beliefs.

He fabricated stories about the suffering

of Catholics at the hands of perverted Communists who beat naked priests

on the testicles with clubs, deafened children with chopsticks to

prevent them from hearing about God, and disemboweled pregnant women. A

graduate of Notre Dame in Indiana, Dooley toured the United States

promoting his books and anti-Communism before he died, in 1964, at age

thirtyfour. One of the last people to visit his sickbed was Cardinal

Spellman, who held up the young physician as an inspiration for all -

another martyr. Dooley's reputation remained untarnished until a Roman

Catholic sainthood investigation in 1979 uncovered his C.I.A. ties."

Dooley had helped the C.I.A. destabilize

North Vietnam through his refugee programs. The Catholics who poured

into South Vietnam provided Diem with a larger political constituency

and were promised U.S.-supported assistance in relocating. The American

public largely believed that most Vietnamese were terrified of the cruel

and bloodthirsty Viet Minh and looked to the God-fearing Diem for

salvation. Many refugees simply feared retaliation because they had

supported the French.

Within his first year in office, however,

Diem became so closely identified with the United States that American

officials grew worried about his effectiveness. This became apparent

when Spellman had Harnett arrange travel plans for him to Vietnam. The

monsignor contacted General L. Collins, head of U.S. military operations

in Vietnam. When he heard of Spellman's proposed visit, the general

became concerned. He cabled Foster Dulles that the Cardinal's presence

would encourage propaganda within Vietnam that Diem was "an American

puppet....... The fact that both Diem and the Cardinal are Catholic

would give opportunity for false propaganda charges that the U.S. is

exerting undue influence on Diem." The general noted, however, that if

Spellman came he could serve a useful purpose, "dramatizing once more

the great exodus of refugees from the North, the greater part of whom

are Catholics." He concluded, though, "I think it would be wiser if he

did not come."40

Spellman wasn't about to be put off. The

Pope had asked him to intervene and he wanted to see the situation

firsthand. His physical presence in Saigon, he knew, would place him and

the Church firmly in Diem's camp in the public mind. When Spellman

arrived at the Saigon airport, he was greeted by a wildly cheering crowd

of about five thousand. The sixty-seven-year-old prelate was once again

dressed in the army khaki attire that he loved to wear in military

zones.

THE AMERICAN POPE

244

Spellman's propagandizing of the [Roman]

Catholic nature of Diem's regime reinforced a negative image of the

[Roman Catholic] Church's position in Vietnam. The sectarian nature of

Diem's government and the problems of that government were noted by the

writer Graham Greene, himself a Catholic, in a dispatch from Saigon

printed in the London Sunday Times on April 24, 1955:

It is Catholicism which has helped ruin

the government of Mr. Diem, for his genuine piety . . . has been

exploited by his American advisers until the Church is in danger of

sharing the unpopularity of the United States.

An unfortunate visit by Cardinal Spellman

["He spoke to us," said a Vietnamese priest, "much of the Calf of Gold

but less of the Mother of God"] has been followed by those of Cardinal

Gillroy and the Archbishop of Canberra. Great sums are spent on

organizing demonstrations for the visitors, and an impression is given

that the Catholic Church is occidental and an ally of the United States

in the cold war.

On the rare occasions when Mr. Diem has

visited the areas formerly held by the Viet Minh, there has been a

[Roman Catholic] priest at his side, and usually an American one

The South, instead of confronting the

totalitarian north with the evidences of freedom, has slipped into an

inefficient dictatorship: newspapers suppressed, strict censorship, men

exiled by administrative order and not by judgment of the courts. It is

unfortunate that a government of this kind should be identified with one

faith. Mr. Diem may well leave his tolerant country a legacy of

anti-[Roman] Catholicism.

During his visit Spellman presented a

check for $100,000 to the [Roman] Catholic Relief Services, which was

active in the refugee-relocation program and later administered a great

deal of the U.S. aid program, which closely bound the CRS to the U.S.

war effort and later led to the suspicion that the CRS had C.I.A. ties.

Turning to the [Roman Catholic] Church to perform such a function was

done in Latin America, among other places, but in Vietnam it eventually

seemed to bear out Graham Greene's warnings that the [Roman Catholic]

Church and the United States were being tied to a cause unpopular among

Vietnamese.

The potential for corruption in Vietnam

was tremendous and also harmed the CRS's reputation. Drew Pearson

estimated that in 1955 alone, the Eisenhower administration pumped more

than $20 million in aid into Vietnam for the [Roman] Catholic refugees.

Though it did a great deal of good, the CRS eventually encountered a

great deal of resentment. Unavoidably, there was much graft and

corruption involved in getting food, medical supplies, and other goods

from ships to villages. By 1976 the National Catholic Reporter, a

hard-nosed weekly newspaper, reported apparent CRS abuses in articles

such as one entitled

"Vietnam 1965-1975. Catholic Relief

Services Role:

Christ's Work - or the C.I.A.'s?"

THE RISE OF AMERICANISM

245

The abuses cited included using supplies

as a means of proselytizing; giving only Catholics aid meant for

everyone; being identified with the military; and giving CRS goods to

American and Vietnamese soldiers rather than to the civilians for whom

the goods were meant.41

Moreover, there was much speculation that

the CRS leadership in Vietnam had C.I.A. links, although this was never

proved.

Long before the National Catholic

Reporter began its investigations, both the U.S. government and Spellman

backed away from the increasingly arrogant and difficult Diem, who, by

the early 1960s, lost support among his people almost daily. Buddhists

held massive protest marches against the government and clashed in the

streets on occasion with Catholics. Finally, on November 2, 1963, Diem

was assassinated during a C.I.A.-inspired coup d'etat.

Two years after the assassination,

Spellman told of his knowledge of Kennedy's involvement to Dorothy

Schiff, the Post publisher, who again visited him at the chancery.

According to her notes:

"He [Spellman] knew that President

Kennedy had been asked to make a decision as to whether or not Diem

would be removed and had decided that it was all right for this to

happen--this on a recommendation from American officials in Vietnam. The

Cardinal said he knew that Kennedy had thought about it overnight,

changed his mind and that he knew that he would have rescinded his

decision of the night before had the event not already taken place and

Diem been dead."42

The publisher was amazed by the

revelation, but there was nothing she could do with the information.

Once again, she had promised not to reveal what she heard at the

Powerhouse. Shortly before the coup Spellman disassociated himself from

Diem. When Bishop Thuc [ Diem's brother .... JP ] visited New York,

Spellman refused to see him, and he personally asked Bishop Fulton Sheen

not to receive Thuc as well. Spellman and Sheen were feuding. Sheen

disregarded Spellman's request and had Thuc to lunch while Spellman

simmered.

Though Spellman backed away from Diem, he

didn't turn his back on Vietnam any more than the U.S. government did.

The Cardinal became one of the most hawkish, arguably the most hawkish,

leaders in the United States. By 1965 he clashed with the Pope, who

desperately tried to bring peace in Vietnam as Spellman pounded the

drums of war.

[papacy plays the role of "peacemaker"

after getting USA into the war in Vietnam on the side of the Roman

Catholic ruling class .... JP]

- END QUOTE - END CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

THE PRINCE OF POWER

246

SPELLMAN EXPECTED DEFERENTIAL TREATMENT

NOT ONLY from legions of politicians and millions of laymen but also

from members of the hierarchy. Indisputably, he did more for the Church

than all the rest of the American hierarchy combined.

His cleverness, contacts, and persistence

enabled the Vatican to play a forceful international role, after

centuries of limited political power. Spellman was the indispensable

source of riches and favors for churchmen in both Rome and America. The

Pope depended on Spellman and the Cardinal could get whatever he wanted.

At times it seemed impossible to tell where the power of the one left

off and that of the other began. It was clear that in America Spellman

was the Church's kingmaker. He bestowed the title "monsignor" with the

regularity of a commander making battlefield promotions, and he made

many bishops in his busy, modern court. If anything, Spellman's power

increased after Pius became ill.

The health of a pope is always taken

seriously. When it appeared in December 1954 that Pius was dying,

Spellman was continually on the telephone to Rome. He had visited the

Pope months earlier when Pius was first suffering from violent bouts of

hiccuping that left him exhausted and unable to hold food down. Spellman

sat by his old friend's side in the Pope's bedroom, with its two windows

overlooking St. Peter's Square and its simple furnishings--a brass bed,

a chest of

-END QUOTE- end page 246

"Spellman và Kennedy cũng đã giúp tạo ra

một cuộc vận động ủng hộ Diệm tại Washington, những cuộc biểu tình phản

đối là chống lại chủ nghĩa cộng sản và Công giáo [La Mã] Qua mối quan hệ

của họ, họ sớm có một ủy ban có quyền lực cao, .

Hai người có tầm quan trọng quốc gia, cựu

giám đốc "Cổng thông tin di sản" Donovan và Tổng "Iron Mike" O'Daniel,

là đồng chủ tịch.

Các thành viên bao gồm Thượng nghị sĩ

John F. Kennedy và Richard Neuberger; Các đại diện Emmanuel Celler và

Edna Kelly; và Angier Biddle Duke, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Max Lerner,

nhà lãnh đạo xã hội chủ nghĩa Norman Thomas, và thống đốc bang Utah

Bracken bảo thủ "

[ trang 242 ]

Có người cố ý bác-bỏ vai trò của Mỹ trong việc ông Ngô Đình

Diệm về nước nhậm-chức Thủ-Tướng, xem như ông ấy là người của Trời,

tự-nhiên mà lên, không được (mà cũng không cần) hậu-thuẫn gì của Hoa Kỳ.

Thế nhưng:

Theo tiến-sĩ PHẠM VĂN LƯU:

“Sau

khi thảo luận với Ông Foster Dulles (Ngoại-Trưởng Hoa Kỳ), để ông ta

biết ý định ấy,

tôi (Bảo Đại) cho vời Ngô Đình Diệm và bảo ông ta: ... Ông cần phải

lãnh đạo Chính Phủ... (trích hồi ký “Con Rồng Việt Nam” của Bảo Đại).

“Đến

ngày 24 và 25 tháng 5 (năm 1954), theo chỉ thị của Hoa Thịnh Đốn, Đại Sứ

Mỹ tại Ba Lê là Dillon và một số viên chức khác đã đến gặp Ông Diệm để

bàn về việc ông nhận chức vụ Thủ Tướng....”

(trước khi ông Diệm về nước vào khoảng 25-6-1954 và nhậm-chức vào ngày

7-7-1954)

(Trích từ cuốn sách “Biến Cố Chính Trị Việt Nam Hiện Đại – Ngô Đình Diệm

và Bang Giao Việt-Mỹ 1954-1963” của Phạm Văn Lưu, do "Centre for

Vietnamese Studies" ở Melbourne, Bang Victoria, Australia, xuất-bản năm

1994 (trang 57)

Theo ông CHÍNH ĐẠO

(tức Nguyên Vũ, Vũ Ngự Chiêu):

“14/6/1954: PARIS: Diệm gặp Đại sứ Mỹ Douglas Dillon, báo tin sắp được

làm Thủ Tướng... Diệm muốn Mỹ viện trợ nhiều hơn để bảo vệ châu thổ

sông Hồng

(FRUS,

1952-1954, XIII:2:1695-6).”

(Trích từ cuốn sách “Việt Nam Niên Biểu 1939-1975 (Tập B: 1947-1954)”

của Chính Đạo, do Văn Hóa, Houston, TX, USA, xuất bản năm 1997, trang

392)

Theo ký-giả TÚ GÀN:

VẤN ĐỀ CHỦ QUYỀN QUỐC GIA

Với một vài nét đại cương chúng tôi vừa trình bày trên, độc giả

cũng có thể nhận thấy rằng người Mỹ đã tốn khá nhiều công sức và tiền

của để xây dựng nên chế độ Ngô Đình Diệm: Từ việc truất phế Bảo Đại, bầu

cử quốc hội, soạn thảo và ban hành hiến pháp, cải cách ruộng đất... đến

việc thành lập một chế độ độc đảng (Cần Lao Nhân Vị Đảng) và cơ quan mật

vụ (Sở Nghiên Cứu Chính Trị)... để có một chính quyền mạnh có thể đương

đầu với cộng sản, các chuyên Hoa Kỳ đã làm việc rất vất vã với chính phủ

Ngô Đình Diệm...

(Xem thêm các mục "Chủ Nghĩa Nhân Vị", "Đảng Cần Lao", v.v...)

Việc thành lập cơ quan mật vụ cho chính phủ Ngô Đình Diệm cũng do

Mỹ đề xướng. Ông Trần Kim Tuyến cho biết chính ông McCarthy, Trưởng trạm

CIA của Tòa Đại Sứ Mỹ ở Sài Gòn đã soạn thảo sẵn văn kiện tổ chức rồi

đưa cho ông Nhu và ông Nhu chuyển cho Bộ Trưởng Phủ Tổng Thống để làm

Sắc Lệnh thành lập “Sở Nghiên Cứu Chính Trị và Xã Hội”... Người đầu tiên

làm Giám Đốc là Đốc Phủ Sứ Vũ Tiến Huân, sau đó mới đến ông Trần Kim

Tuyến...

(Trích từ bài viết “Trả lại sự thật cho lịch sử” của Tú Gàn - Saigon Nhỏ

ngày 26.10.2007)

Theo ông THOMAS L. AHERN, JR.

(tác-giả “CIA and the House of Ngo: Covert Action in South Vietnam,

1954-1963” do CIA xuất-bản):

“Qua tài liệu này, lần đầu tiên chúng ta biết được, từ năm

1950 cho đến năm 1956, CIA có hai Sở tình báo ở Sài Gòn: một Sở CIA

Saigon Station nằm dưới sự điều khiển thông thường từ bản doanh CIA ở

Langley, Virginia; Sở kia, có tên là Saigon Military Mission, làm việc

trực tiếp, và chỉ trả lời cho Giám Đốc Trung Ương Tình Báo. Saigon

Military Mission, theo Tài Liệu Ngũ Giác Đài (The Pentagon Papers) được

giải mật trước đây, do đại tá Edward G. Lansdale chỉ huy. Lansdale đến

Sài Gòn tháng 6-1954 (ông Ngô Đình Diệm về nước vào cuối tháng 6.1954)

với hai nhiệm vụ: huấn luyện những toán tình báo Việt Nam để gài lại ở

miền Bắc trước ngày di cư và tập kết hết hạn; và, dùng mọi phương tiện

ngầm (covert action) để giúp tân thủ tướng Ngô Đình Diệm (nhậm chức từ

7-7-1954). Theo tác giả Thomas L. Aherns, chính Giám Đốc CIA Allen

Dulles chỉ định đại tá Lansdale cho điệp vụ ở Sài Gòn và cũng ra lệnh

Lansdale làm việc trực tiếp cho ông. Tác giả Ahern viết, CIA có mặt từ

năm 1950 để giúp đỡ quân đội Pháp xâm nhập và thu thập tin tức tình báo.

Nhưng từ cuối năm 1953, khi thấy tình hình quân sự nguy ngập của Pháp,

Hoa Thịnh Đốn thay đổi nhiệm vụ của CIA Saigon Station: Liên lạc và thu

thập tình báo những thành phần quốc gia để lập một chánh thể chống cộng

trong trường hợp Hoa Kỳ thay thế Pháp. Cùng lúc Hoa Thịnh Đốn gởi thêm

một toán CIA để lo về quân sự, Saigon Military Mission...

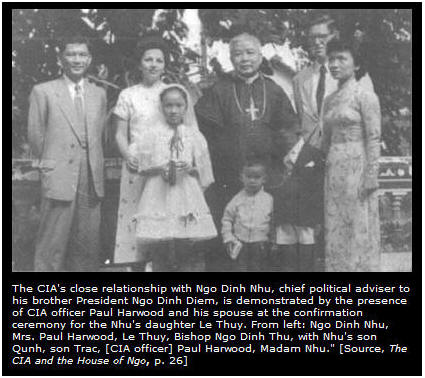

CIA and the House of Ngo tiết lộ một số chi tiết ly kỳ như,

CIA liên lạc và làm thân với ông Ngô Đình Nhu từ năm 1951, rất lâu trước

khi Hoa Kỳ liên lạc với ông Diệm. Đầu năm 1954, khi có tin Hoa Kỳ chuẩn

bị đề nghị quốc trưởng Bảo Đại và chánh phủ Pháp giải nhiệm hoàng thân

Bửu Lộc và thay bằng ông Diệm, thì ông Nhu là người đầu tiên CIA gặp để

bàn về liên hệ của Hoa Kỳ đối với thủ tướng tương lai Ngô Đình Diệm.

Tháng 4-1954, một nữ nhân viên Mỹ làm việc ở CIA Saigon Station, thông

thạo tiếng Pháp, quen biết và liên lạc thân thiện với Bà Ngô Đình Nhu.

Từ nữ nhân viên Virginia Spence này, Sở CIA Saigon bắt được nhiều liên

lạc với hầu hết những người thân trong gia đình, hoặc thân cận với Nhà

Ngô.

Tháng 4-1954, CIA ở Hoa Thịnh Đốn gởi Paul Harwood sang làm cố vấn riêng

cho ông Nhu. Tuy là nhân viên CIA, nhưng Harwood đóng vai một nhân viên

Bộ Ngoại Giao, làm việc từ Tòa Đại Sứ. Trong hai năm, Hardwood cố vấn là

làm việc với ông Nhu để xâm nhập và ảnh hưởng đường lối ngoại giao quân

sự của nền đệ nhất VNCH với tổng thống Diệm. Paul Hardwood thân thiện

với gia đình ông bà Nhu đến độ ông ta là người đỡ đầu cho Ngô Đình Lệ

Thủy, ái nữ của ông bà Nhu...”

(Trích từ "CIA and the House of Ngo: Covert Action in South Vietnam,

1954-1963" [Tài liệu mật của CIA về gia đình họ Ngô] của Thomas L.

Ahern, Jr. do Center for the Study of Intelligence (CIA) ấn hành, Nguyễn

Kỳ Phong lược dịch)

Vietnam Statistics - War Costs: Complete Picture Impossible

An article from CQ Almanac 1975

The total cost of the Vietnam War is impossible to determine.

Although the Defense Department reported that the U.S. military share of

the Southeast Asian conflict would total $138.9-billion for the period

1965–76, no figures are available on the exact amount of economic and

military assistance channeled to Vietnam since 1950, when the United

States agreed to give arms aid to the French-sponsored states of

Indochina. Even if a grand total were available, it would only reflect a

part of the true price of the war.

Veterans benefits, for example, were expected to reach a $33-billion

level by 1980. But beyond that year there was uncertainty. Government

estimates placed the eventual cost of benefits above the amount spent by

the Pentagon in Vietnam. The ultimate figure would depend on how many

veterans bought homes with VA mortgages, were hospitalized at government

expense or took advantage of education grants.

And beyond the military expenditures and veterans benefits were the

intangibles that defy cost analysis—lost human lives, disabled bodies,

displaced persons and devastated countrysides.

“The impact of Vietnam is so gigantic and diffuse that no adequate

calculation of all the political, sociological and economic costs can be

made,” said Dennis Mueller of Cornell University in 1970.

Barry Blechman, a senior fellow in foreign policy at the Brookings

Institution, assessed the cost of the war this way:

“The real cost, the most damaging costs are not quantifiable—they are

the effects on attitudes here in this country, on our conceptions, and

the effect these will have on our policies. We have a whole generation

of [young] people who mistrust the government, who won't have anything

to do with the government.”

Military Costs

Although the Pentagon estimated that military expenditures for the

Vietnam war between fiscal 1965 and 1974 amounted to $138,974,000,000,

the department noted that a large portion of that sum would have been

spent in any event. The department prepared another total, called “war

costs only,” that came to $110.7-billion and represented expenditures

that would not otherwise have been made. (Details, box this page.)

To make the Defense Department statistics comprehensible

to the public, James

L. Clayton of the University of Utah made

several comparisons.

The war cost 10 times more than support for all levels of education and

50 times more than was spent for housing and community development

during that same period, Clayton said. The United States spent more

money on Vietnam in 10 years than it spent during the nation's entire

history for public higher education or for police protection.

Government Costs

In 1974, the Library of Congress reported that there had been no

official study of the long-range cost of the Vietnam conflict. The U.S.

Statistical Abstract, however, placed the final government cost at

$352-billion, and private economists double or triple this amount.

Taking the highest estimates, it has been calculated that the United

States could have paid off the mortgage on every home in the nation and

had money left over had there been no Vietnam War. Surprisingly,

Congress had not compiled figures on the total cost of the war as of

April 1975. The House Defense Appropriations Subcommittee, for example,

told a Boston Globe reporter that the figure was “hard to get a

handle on” because of “sloppy bookkeeping” at the outset of the nation's

involvement in Vietnam.

Lost Equipment

The Pentagon, however, has kept accurate records on one cost of the

war—the number of U.S. aircraft lost between 1961 and 1973. A total of

3,699 fixed wing planes were lost in combat or accidents during the

period, while 4,865 helicopters were written off.

Secretary of Defense James

R. Schlesinger in testimony before the

Senate Foreign Relations Committee April 15 estimated the cost of U.S.

equipment in South Vietnam through mid-April as $3-billion to $4-billion

based on original cost figures, although he said much of the equipment

was damaged.

He also estimated that equipment left behind by South Vietnamese forces

during their withdrawal from some southern provinces had cost more than

$800-million. Final accounting, he added, probably would push that

figure above $1-billion.

War Casualties

At least 1.5 million persons including civilians died in the Indochina

conflict. U.S. combat losses totaled 46,463; another 10,355 died from

non-hostile causes. A total of 303,704 were wounded. South Vietnam

battle deaths totaled more than 196,000 and enemy deaths about a

million.

(Box, p. 297)

Figures on American casualties were compiled by the Defense Department.

The South Vietnamese command provides its own and enemy casualty

estimates.

The highest number of combat deaths in U.S. history was recorded in

World War II, when 291,557 were said to have lost their lives. In other

modern conflicts the death toll was recorded as 53,402 in World War I

and 33,629 in the Korean conflict.

The war toll among civilians is much more difficult to estimate.

Statistics are sparse.

The following table, a composite of estimates made by the Agency for

International Development and the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on

Refugees and Escapees, [1]

indicates some of the war's effect on the civilian population in South

Vietnam. [2]

|

Year

|

AID Est. War Casualty Hospital Admissions

|

Subcommittee Casualty Est. Including Deaths

|

Subcommittee Death Estimates

|

|

1965

|

50,000 [2]

|

100,000

|

25,000

|

|

1966

|

50,000 [2]

|

150,000

|

50,000

|

|

1967

|

46,774

|

175,000

|

60,000

|

|

1968

|

80,359

|

300,000

|

100,000

|

|

1969

|

59,222

|

200,000

|

60,000

|

|

1970

|

46,247

|

125,000

|

30,000

|

|

1971

|

38,325

|

100,000

|

25,000

|

|

1972

|

53,367

|

200,000

|

65,000

|

|

1973

|

43,218

|

85,000

|

15,000

|

|

1974

|

41,525

|

3

|

3

|

|

1975 [4]

|

3,661

|

3

|

3

|

|

TOTAL

|

512,698

|

1,435,000

|

430,000

|

|

[1] Report of Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Refugees

and Escapes, Humanitarian Problems in South Vietnam and

Cambodia: Two Years After the Cease-Fire, Jan. 27, 1975.

|

|||

|

[2] Figure supplied by Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on

Refugees and Escapees.

|

|||

|

[3] Estimates not available.

|

|||

|

[4] 1975 figures through January only.

|

|||

Chronology

United States involvement in Indochina dated back to 1950 when

Washington initiated a program of military assistance to French

Indochina. Following is a chronology of major developments through the

series of Communist victories in Cambodia and South Vietnam in early

1975:

1950

Aug. 10—The first shipload of U.S. arms aid to

pro-French Vietnam arrives.

1954

May 7—Viet Minh overrun French fortress at Dienbienphu.

1955

Feb. 12—First American military advisers are dispatched

by the Eisenhower administration for the purpose of training the South

Vietnamese army.

1961

May 13—President Kennedy orders 100 specially trained

jungle fighters (Special Forces) to South Vietnam.

Dec. 22—Specialist 4 James Davis of Livingston, Tenn.,

killed by Viet Cong; later called by President Johnson “the first

American to fall in defense of our freedom in Vietnam.”

1963

Nov. 1—South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem and his

brother are assassinated outside of Saigon. One coup d'etat follows

another and weakens the nation's ability to maintain its war effort.

1964

Aug. 2—U.S. destroyers Maddox and C. Turner Joy are

reported attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats in the Gulf of

Tonkin.

Aug. 7—Congress approves Gulf of Tonkin resolution

affirming support of “all necessary measures to repel any armed attack

against the forces of the United States…to prevent further

aggression…(and) to assist any member or protocol state of the Southeast

Asia Collective Defense Treaty requesting assistance….” The Senate vote

was 88-2; the House vote was 414-0.

1965

Feb. 7—President Johnson announces joint U.S. and South

Vietnamese air attacks against the North Vietnamese staging areas “in

response to provocation ordered and directed by the Hanoi regime.”

Dec. 24—United States begins bombing moratorium over

North Vietnam.

1966

Jan. 31—Johnson announces that U.S. aircraft have resumed

bombing targets in the North after a 37-day pause.

June 29—United States begins bombing in the immediate

vicinity of Hanoi and Haiphong—considered to be a major escalation of

air war.

1967

Sept. 3—Chief of State Nguyen Van Thieu elected

president of South Vietnam.

1968

Jan. 30—Communist troops start Tet offensive which

escalates into one of the major battles of the war, including attacks on

almost all the capitals of South Vietnam's 44 provinces.

Oct. 31—Johnson announces a complete halt of the

bombing of the North effective Nov. 1.

1969

Jan. 18—Expanded peace talks open in Paris with

representation by the United States, South Vietnam, North Vietnam and

the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong).

June 8—At a conference with Thieu on Midway Island,

Nixon announces the first planned troop withdrawal.

1970

April 30—President Nixon announces incursion by U.S.

and South Vietnamese forces into Cambodia to destroy border area

sanctuaries.

1971

Jan. 13—President signs bill repealing Gulf of Tonkin

Resolution.

Oct. 3—Thieu re-elected president of South Vietnam.

Dec. 26–30—United States carries out the heaviest air

raids on North Vietnam since 1968 in retaliation for Communist buildup

and offensive.

1972

Aug. 12—The last units of U.S. combat troops leave

South Vietnam.

Oct. 26—Presidential

adviser Henry

A. Kissinger announces at a White House

press conference that the United States and North Vietnam are in

substantial agreement on a nine point peace settlement, disclosed

earlier the same day in a Hanoi broadcast.

Nov. 1—In a broadcast marking South Vietnam's National

Day, President Thieu denounces the draft peace agreement as “a surrender

of the South Vietnamese people to the Communists.”

Dec. 4—Kissinger and Le Duc Tho, chief adviser to the

North Vietnamese delegation, resume private peace talks in Paris.

Dec. 13—Kissinger-Tho talks recess with no agreement.

Dec, 16—Kissinger tells White House press conference

that the secret talks in Paris were suspended because Hanoi changed its

position on several points in the agreement negotiated by the two sides.

Dec. 18—U.S. begins heaviest bombing of North Vietnam,

resuming strikes above the 20th Parallel in North Vietnam and mining of

North Vietnamese harbors.

Dec. 30—The White House announces that President Nixon

has ordered an indefinite halt to the bombing above the 20th Parallel in

North Vietnam, and that Kissinger and Tho will resume negotiations in

Paris Jan. 8. Bombing continues in the southern “panhandle” section of

North Vietnam.

1973

Jan. 8—Kissinger and Tho resume private talks.

Jan. 14—Gen, Alexander

M. Haig Jr., Army vice-chief of staff,

travels to Saigon to consult with President Thieu on the progress of the

cease-fire negotiations.

Jan. 16—The White House announces the suspension of

bombing and all other offensive action throughout North Vietnam, citing

“progress” in the Paris negotiations.

Jan. 27—Formal signing of peace agreement in Paris by

U.S., South Vietnam, North Vietnam and Viet Cong's provisional

revolutionary government.

Feb. 12—North Vietnam and Viet Cong begin releasing

U.S. prisoners of war.

March 29—North Vietnam releases the final 67 American

prisoners of war, and the United States withdraws its remaining 2,500

troops from South Vietnam, officially ending American military

involvement in Vietnam.

July 1—President Nixon signs a supplemental

appropriations bill setting an August 15 cutoff date for all U.S. combat

activities in or over Cambodia, Laos, North Vietnam and South Vietnam.

Nov. 7—Congress overrides President Nixon's veto of a

bill limiting to 60 days the president's authority to commit U.S. troops

abroad and permitting Congress to end such a commitment on its own

initiative.

1974

April 16—South Vietnam announces suspension of

political talks with the Viet Cong because of what it calls an

increasing number of truce violations by the Communists.

July 30—Congress votes a $1-billion ceiling on military

aid to Vietnam, $600-million less than requested by the administration.

Aug. 19—President Ford announces plans for an amnesty

program of “earned re-entry” for Vietnam war deserters and

draft-dodgers.

Sept. 18—The last known U.S. prisoner of war in

Indochina, Emmet James Kay, is released in Laos by the Pathet Lao.

1975

Jan. 28—President Ford asks Congress for $522-million

in emergency military aid for South Vietnam and Cambodia.

Feb. 24-March 2—At the request of President Ford, an

eight-member congressional delegation visits Cambodia and South Vietnam

to assess the military and economic situation. On return, the majority

recommends emergency economic aid and military supplies.

March 5—North Vietnamese forces launch major attack in

Central Highlands of South Vietnam.

March 17—South Vietnam begins abandoning eight

provinces—40 per cent of the country—in a retreat that precipitates

refugee flights and panic throughout the country.

April 1—President Lon Nol leaves Cambodia to clear way

for possible negotiations between his successor government and Khmer

Rouge insurgents.

April 8—Army Chief

of Staff Frederick

C. Weyand returns from mission to Saigon

for President Ford and reports that South Vietnam “still has the spirit

and the capability to defeat the North Vietnamese.”

April 9—The White House discloses that former President

Nixon had given South Vietnam private assurances that the U.S. would

“react vigorously” to any major Communist violation of the cease-fire.

April 10—President Ford asks Congress for $722-million

in emergency military aid for South Vietnam and $250-million for

economic and humanitarian aid.

April 16—Cambodian government in Phnom Penh surrenders

to Communist-led Khmer Rouge forces. In Vietnam, American officials

organize evacuation of U.S. citizens from Saigon.

April 21—South

Vietnam President Nguyen Van Thieu resigned from office. In an angry

speech, Thieu accuses the United States of breaking its promises to

support an anti-Communist South Vietnamese government. “The United

States has not respected its promises. It is unfair. It is inhumane. It

is not trustworthy. It is irresponsible,” he declared. According to

Thieu, former President Richard

M. Nixon promised the United States would

always stand ready to help South Vietnam in case the Communists violated

the 1973 peace accord. “…I won a solid pledge…that when and if North

Vietnam renewed its aggression, the United States would actively and

strongly intervene,” Thieu said.

South Vietnam Vice President Tran Van Huong is appointed president by

Thieu, who explained that the U.S. Congress was considering additional

aid for the war-torn nation and he hoped his resignation would favorably

influence the outcome of that debate.

In a televised interview April 21 with three CBS correspondents,

President Ford says that the U.S. government “made no direct request”

that Thieu step down. Asked to reply to Thieu's comment that the United

States had led the South Vietnamese people to their deaths, President

Ford says there were “some public and private commitments” made in

1972-73 whereby the United States promised to try to enforce the Vietnam

peace agreement. “Unfortunately, the Congress in August 1973…took away

from the President the power to move in a military way to enforce the

agreements that were signed in Paris,” Ford says. “I can understand his

[Thieu's] observations.”

The failure of Congress to appropriate $300-million authorized in 1974

for assistance to Vietnam raised doubts in the minds of the South

Vietnamese that the United States would be supplying sufficient military

aid for defense against the North Vietnamese, Ford adds.

“The lack of support certainly had an impact on the decision that

President Thieu made to withdraw precipitously [from northern

provinces]. I don't think he would have withdrawn if the support had

been there….”

April 22—President Thieu's resignation, which U.S.

officials had hoped would lead to a cease-fire and negotiations by the

North Vietnamese and Vietcong, appears to have no impact on enemy

military thrusts.

In Paris and Hanoi, the Hanoi, the Vietnamese Communists say that the

United States must “abandon the Nguyen Van Thieu clique and not just the

person of Nguyen Van Thieu” as a step to a political settlement in South

Vietnam.

April 23—President Ford in a speech at Tulane

University urges the American people to put the Vietnam War behind them

and to avoid recriminations and bitter debate over how the war was lost.

“I ask tonight that we stop refighting the battles and recriminations of

the past,” Ford says. He appeals for “a great national reconciliation”

and for a new effort to regain “the sense of pride that existed before

Vietnam.”

April 28—Gen. Duong Van Minh is sworn in as president

of South Vietnam, replacing Tran Van Huong who had held the office one

week.

The U.S. evacuation of South Vietnamese and Americans continues as

Communist troops shell Tan Son Nhut air base outside Saigon.

Late in the evening, President Ford orders the immediate evacuation of

all Americans from Saigon after the airport is closed by Communist fire

and unruly crowds.

A bill (H J Res 407) to appropriate $165-million in military assistance

to South Vietnam is removed from the House calendar, thus dropping it as

an item to be considered.

April 29—House

Rules Committee member James

J. Delaney (D N.Y.) announces, while the

final evacuation was under way, that he had been instructed by Speaker Carl

Albert (D Okla.) to remove the conference

report on the Vietnam assistance-evacuation bill (HR 6096—H Rept 94–176)

from the calendar.

The evacuation is completed at 7:52 P.M., ending the American presence

in South Vietnam. Ford says the final' withdrawal “closes a chapter in

the American experience.” In the final removal, approximately 1,000

Americans and 5,500 South Vietnamese are ferried by helicopter from

Saigon to waiting U.S. carriers in the South China Sea.” Four U.S.

Marines are killed in the final withdrawal.

Within hours of the announcement in Washington of the completion of the

evacuation, President Minh in Saigon announces the unconditional

surrender of South Vietnam.

April 30—The Senate Foreign Relations Committee orders

reported a bill (S 1541) authorizing $50-million for Cambodian relief.

May 1—After a two-day delay, the House takes up and

rejects by a vote of 162–246 the conference report on HR 6096.

Features

Vietnam War Costs, 1965–75

Following are Defense Department estimates of the cost of the Vietnam